Who doesn’t love the Beatles?

I didn’t, at least not until later in high school.

I dismissed the band, not out of a genuine dislike of their music but for the same reason I rejected Britney Spears and Abercrombie and Fitch: I was pretentious. Like most insufferable hipsters in the early 2000s, I detested anything mainstream: I shopped at thrift stores, obsessed over obscure bands and automatically loathed anything on MTV.

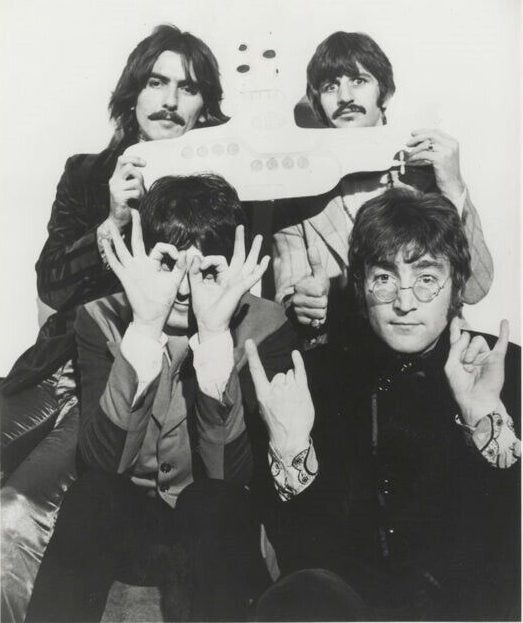

The Beatles are the epitome of mainstream. They are almost unanimously considered the best band in human history: in the short span of 7 years, they released 13 studio albums and had 20 #1 hit singles. They’re the best-selling music act of all time, with estimates suggesting they’ve sold over 500 million albums. Their influence is impossible to overstate: whether you were born in 1940 or 1990, you have memories of these quick-witted lads from Liverpool. Maybe you sat around a campfire singing “Yellow Submarine”; maybe your dad played “Breakfast with the Beatles” on the radio every Saturday morning; or maybe “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away” ripped open a revelation about human intimacy when you were high on ecstasy (this may or may not be inspired by a true story). No matter who you are, you can’t seem to escape the Fab Four’s charming mop tops and catchy melodies.

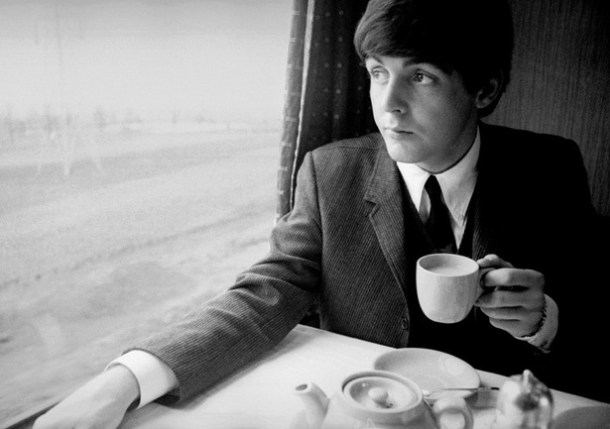

For reasons I still don’t quite understand, when I was 15, I bought my first Beatles record: Rubber Soul. I liked the psychedelic orange font of the title, their longer, hippie-like hair. They looked moodier, edgier, not as pop star palatable as the smiling, suited band on the Please Please Me cover. Though I was listening to the album 40 years after it was first released, it somehow still felt relevant. One song that spoke to me in my early 2000s teenage angst was McCartney’s “You Won’t See Me,” a deceptively cheery-sounding tune that recounts his troubled relationship with long-time girl friend Jane Asher.

Critics were divided on the song: while Niki Wine of KRLA Beat called it “one of the greatest arrangements and blending of melodies,” Richard Green of the Record Mirror slammed the song, saying it “had none of the old Beatles excitement and compulsiveness” and was “dull and ordinary.”

Rubber Soul was a transitional record that marked a moving away from the energetic rhythms and easily digestible pop songs of early Beatlemania. I personally loved their new sound especially as it was represented in “You Won’t See Me.” Unlike early songs that capture the simplicity of young love (“Love Me Do”/”I Want to Hold Your Hand”), “You Won’t See Me” demonstrates McCartney’s growing maturity as a lyricist. The song recalls the agony of a loved one refusing to take your calls, the many misunderstandings and miscommunications that occur over the course of a relationship. This wasn’t the uncomplicated giddiness of a first crush—it was the complicated reality of actually loving someone (and despite what Mr. Green says, it still has that signature Beatles catchiness). When my high school boyfriend gave me the silent treatment after one of our many arguments, I dramatically put McCartney’s despondent lyrics as my AIM away message.

Today I realize why the Beatles have such enduring appeal: their music captures something universal.

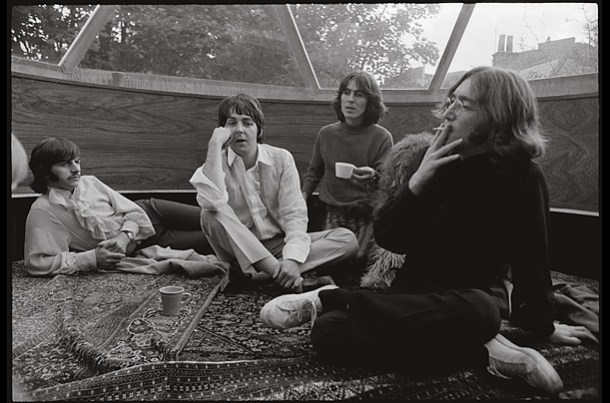

If you’re a devout fan of the Fab Four or just interested in the intersection of the particular and universal, I highly recommend In Their Lives, a heartfelt and high-spirited compendium of essays from “a chorus of twenty-nine luminaries” who sing “the praises of their favorite Beatles songs.” Contributors include Roseanne Cash (“No Reply”), Jane Smiley (“I Want to Hold Your Hand”), Pico Iyer (“Yesterday”) and Chuck Klosterman (“Helter Skelter”). An irresistible blend of music criticism and personal memoir, In Their Lives explores the history behind the making of each song and the history of each listener. As one Guardian critic notes, the Beatles are a musical madeleine, their songs sensory triggers evoking memories of formative moments in each writer’s life. Some reminisce about their first love or first kiss or first time they did acid; others contemplate the disintegration of their parents’ marriage.

One of my favorite essays was “Yellow Submarine” by the incomparable Maria Popova, poet, essayist, cultural critic and founder of the one-of-a-kind blog Brainpickings. In her essay, she argues art has no singular meaning and pop culture is the screen onto which we project our own stories.

For Popova, the Beatles’ carefree, childlike song epitomizes the ways we try to fill impossible-to-interpret works of art with subjective sense. She explores the background behind the making of “Yellow Submarine” and the many spirited and somewhat silly debates about its meaning (“Was it an ode to psychedelics? Or was it a criticism of the war in Vietnam?). Though McCartney has always insisted “Yellow Submarine” was an innocuous children’s tune, generations of critics still try to find sense in the senselessness of the song. The submarine beneath the “sky of blue” and “sea of green” couldn’t just be a submarine—it was a “pathetic paean of white privilege” or a condemnation of materialism. Music critic Jim Beviglia aptly called “Yellow Submarine” a musical Rorschach test where we make our own meaning out of the inky meaninglessness.

So what are some writing lessons we can take away from Popova’s expertly-executed essay?

Let’s take a look at the beginning:

“My parents fell in love on a train. It was the middle of the Cold War and they were both traveling to their native Bulgaria to Saint Petersburg in Russia, where they were to attend different universities—my father, an introvert of formidable intelligence, was studying computer science; my mother, poetry-writing (bordering-on-bossy) extrovert, library science.

An otherwise rational man, my father describes the train encounter as love at first sight. Upon arrival, he began courting my mother with such subtlety that it took her two years to realize she was being courted.

One spring morning, having finally begun to feel like a couple, they were walking across the lawn between the two dorms and decided it was time for them to have a whistle-call. At the time, Bulgarian couples customarily had whistle-calls—distinctive tunes they came up with, usually borrowed from the melody of a favorite song, by which they could find each other in a crowd or summon one another across the street.

Partway between the primitive and the poetic, between the mating calls of mammals and the sonnets by which Romeo and Juliet beckoned each other, these signals were part of a couple’s shared language, a private code to be performed in public.

[…]

That spring morning, knowing my mother was a Beatles fan, my father suggested “Yellow Submarine.” There was no deliberation, no getting mired in the paradox of choice—just an instinctive offering fetched from some mysterious mental library.”

What I love most about Popova’s writing is it always sounds like she’s having fun. She writes in the spirit of a child playing in a sandbox. There’s no sense of burdensome duty or joyless obligation: she’s just a curious child constructing sandcastles. “There’s really nothing less pleasurable to read than embittered writing,” Popova once said in an indispensable interview with Tim Ferris. She goes on to quote witty, warm-hearted Kurt Vonnegut, “Write to please just one person.”

Popova clearly takes Vonnegut’s advice. She never writes for a publisher or preconceived audience. She doesn’t churn out “content” nor does she prioritize profit (Brainpickings has been famously free of advertisers since its inception). She doesn’t chase clicks or views or virality. She writes for her own pleasure and her own pleasure only.

Popova never resorts to the convenient cliche. A cliche is like the missionary position: something you’ve done so many times that it’s lost all excitement or passion. The writer’s job is to seduce us with language. They seduce—not by relying on the same shopworn cliches and recycled images, the verbal equivalent of making love tepidly in the most routine and unimaginative sexual positions—but by finding the freshest modes of expression. A good writer surprises us with handcuffs and blindfolds, tantalizes us with a spritz of racy redcurrant perfume by Carolina Herrera. Popova always writes with imagination. When her father suggests “Yellow Submarine,” he doesn’t simply recollect the iconic Beatles song—he “fetch[es] it from some mysterious mental library.”

Popova has a poet’s appreciation for language’s musical quality and a storyteller’s sense of pacing. Take the essay’s first sentence: “My parents fell in love on a train.” Immediately, we’re captivated by the sentence’s short simplicity. Popova elegantly balances clarity and curiosity: though the first sentence is grounded in concrete nouns (“parents”/”train”), these people and places are just general enough to stimulate our curiosity. Who are her parents? Where are they going?

The next sentence begins disentangling these mysteries.

We learn her mother and father are both university students on the way to Saint Petersburg. What could have been a bland recitation of background information is made more pleasurable by Popova’s command of language. The characterization of her genius engineer father (“an introvert of formidable intelligence”), for instance, contains a lovely assonance (“introvert”/”intelligence”) and consonance (“father”/”formidable”). She brings this inventiveness to the description of her mother, concocting entirely new words with hyphens (“poetry-writing”/”bordering-on-bossy”).

Much like the band who is her subject matter, Popova knows how to connect the universal to the particular. Throughout her masterful essay, she interweaves cultural criticism and personal history. Rather than restrict herself to the objective, analytical voice of the music critic, she writes in “I,” the personal 1st person. In the first eleven paragraphs, she tells the story of what “Yellow Submarine” means for the members of her family: for her astronomer/mathematician great great grandfather, barricaded behind the Iron Curtain, “Yellow Submarine” represented a revolutionary act of intellectual insurgency; for her father, the boisterous ditty recalled both the love of his life and his boyhood obsession with the sea.

But why tell her own story?

By telling the sweeping saga of her immigrant family, Popova makes her essay more engaging. Humans are quite literally hardwired for story: we crave a set of events arranged in neat narrative order, a conflict driving itself toward climax and conclusion.

If we want to illustrate a point or convince someone of our point-of-view, we usually think we should 1) strive to be as objective as possible and 2) cram our writing with concrete facts and figures. However, studies show stories are remembered 22 times more than facts alone. Whereas a bullet point list or paragraphs of purely factual information trigger the language processing parts of the brain, a story activates many regions and makes us feel like we’re actually experiencing the story ourselves.

If a writer describes the pink tangerine stains of a spring sunset, our sensory cortex lights up. Similarly, if they describe the scent of a coastal breeze steeped in eucalyptus or coffee and blueberry pancakes or Chanel No 5 perfume, our olfactory cortex goes off.

Writers are sorcerers: summoning entire worlds. Detailed descriptions, evocative characterizations, a never-before-seen metaphor can transport our readers somewhere else. When they read about an experience, they experience the experience, which makes it all the more memorable.

Popova could have simply stated her central claim and substantiated it using the Beatles’ nonsensical song. But she makes her claim more compelling by harnessing storytelling’s primitive power. Now anytime I hear “Yellow Submarine,” I’ll think of the impossibility of interpretation and her parents’ whimsical whistle call.