Since I finished my last project a few weeks ago, I haven’t felt compelled to put pen to page. I was stuck in limbo: what did I want to write next? what did I even have to say?

I felt myself oscillating between two contradictory impulses: the instinct to wait for the muse’s mysterious reappearance and the urge to go after the next idea like Ernest Hemingway hunting big game. I know from experience that writing creates the mood: oftentimes we won’t feel like we have anything to say until we sit at the page. The actual act of writing opens the floodgates.

Yet I felt hesitant to start anything new. I didn’t feel “called” to write about anything. I had ideas but nothing that felt important or necessary. There was nothing I had to commit to the page.

So what do you do when you’re not sure what to write next: push forward or sit and wait?

Brandi Reissenweber recommends waiting, no matter how hard it might be. Like planting a garden, writing takes time. You can’t force seeds to germinate.

But there are certain things you can do while you’re waiting:

write

Even if you haven’t landed on your next big idea, write anyway. I always had this idea that I could only write if I was writing SOMETHING (i.e. something that would take the form of a final product like a book or an essay or a short story). But as Austin Kleon says in Keep Going, you can jam without recording a song, you can draw a doodle and throw it away, you can paint something with no intent of hanging it in an art gallery.

In the same way, you can write without knowing where you’re going. You can write without having a concrete conception of the final product, you can free associate without having to arrange words into a polished piece. Sometimes writing is all it takes for an idea to take root and start growing.

So free write, make lists, scribble furiously in your diary. Ask yourself: what do you love? loathe? what makes you angry? Let the page be your sandbox. Play without the pressure of knowing where you’re going or what—exactly—you’re going to write about. Sometimes writing in a free, unstructured way is all you need for the muse to reveal herself.

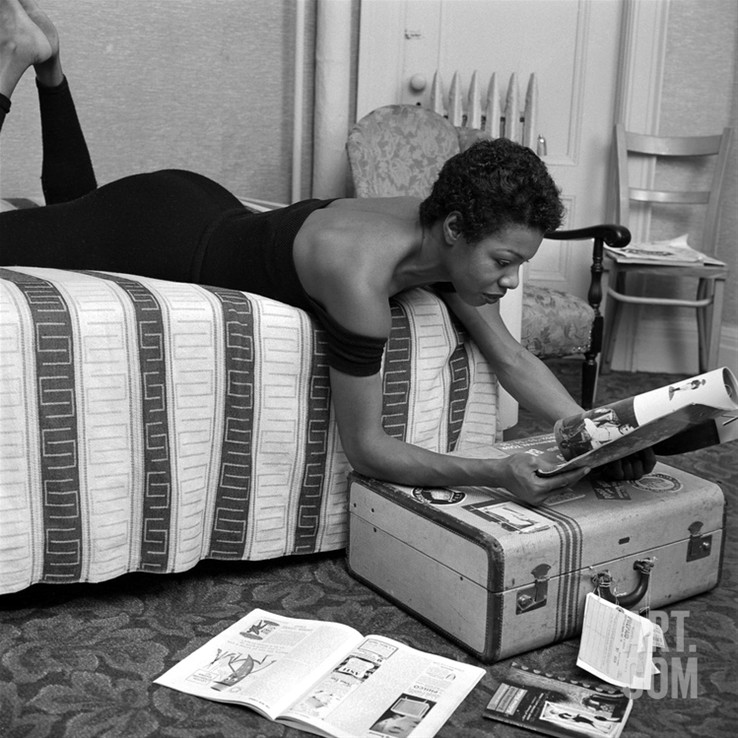

read

“Writing comes from reading,” Annie Proulx once observed. Virginia Woolf put it more poetically: “Read a thousand books and your words will flow like a river.” Ray Bradbury believed reading was compost for creativity: “If you stuff yourself full of poems, essays, plays, stories, novels, films, comic strips, magazines, music, you automatically explode every morning…I have never had a dry spell in my life, mainly because I feed myself well, to the point of bursting.”

Maya Angelou always kept the Bible at her writing desk to remind herself how beautiful English is. Susan Sontag would spend 8-10 hours a day reading (though in a series of commandments in her 1977 diary, the crowning cultural critic resolved to confine [her] reading to the evening because she read too much “as an escape from writing.”)

Lesson? If you’re feeling uninspired, read. Reading can reinvigorate your own process and make you see language in all its glorious possibility. Savor sumptuous sentences. Feast on imaginative figures of speech. Delight in delicious turns-of-phrase. Let the genius of other wordsmiths nourish your own writing.

get moving

Literary history abounds with stories of avid walkers. Revered romantic poet William Wordsworth is estimated to have written 400 poems and walked an impressive 175,000 miles in his 80 years (“The act of walking is indivisible from the act of making poetry: one begets the other,” he once argued). Philosopher and naturalist Henry David Thoreau believed thinking and walking were intimately intertwined (“The moment my legs begin to move, my thoughts begin to flow,” he wrote in his journal almost two hundred years ago). Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard agreed: “I walked myself into my best thoughts.”

These enthusiastic walkers make you wonder: is there a connection between walking and writing output?

For me, the answer is a resounding “yes.”

If you’re stuck at a difficult impasse in a sentence, if you’re waging a battle with the blank page, give up fighting and get up from your desk. Take a spirited saunter through some redwood trees or treat yourself to a serene stroll by a New England lake. Frolic in a dandelion-dotted meadow or tramp through crowded city streets. Watch the clouds swirl across a Renoir blue sky. Listen to the crunch of autumn leaves beneath your feet.

We can walk into new thoughts when we walk into new landscapes. Liberated from our ordinary settings (i.e. our writing desk strewn with crumpled papers and mugs of day-old coffee), we’re liberated from our customary ways of thinking. The mechanical, almost mindless movement of putting one foot in front of the other occupies our conscious minds so our more imaginative unconscious can wander more freely (As Rebecca Solnit once observed, “Walking allows us to be in our bodies and in the world without being made busy by them. It leaves us free to think without being wholly lost in our thoughts”).

In one Stanford study, walking was shown to boost creative output by an astounding 60 percent. So strap on your hiking boots and abandon the confinement of your desk.

remember: writing occurs in seasons, not linearly

In the end, writing comes in cycles, in seasons, in waves. Writers don’t write all the time. Yes, they write most days but they’re not always working on something. After completing a big project, it’s normal to take a well-deserved break. Novelist, memoirist, and all around large-hearted human being Elizabeth Gilbert describes her process as seasonal. Some seasons she writes in a feverish fury; other seasons she doesn’t write at all. When she first begins a project, she usually spends months simply reading and researching. Only when she feels ready does she actually begin writing. “Months and years can pass between bouts of writing,” she confesses, “But when it comes time to write, I keep farmer’s hours. Up before dawn, and I work until about 11:00 or noon every day.”

So remember: some seasons are for gestating an idea, for cultivating the soil, for planting seeds; others are for harvesting.

give yourself grace

Our culture loves to count and compute and calculate. We’re obsessed with outcomes. We think something is only worthwhile if it can be quantified or packaged as a final product. For us, progress is linear and discernible. If we’re “making progress” on writing, we’re producing words on a page. If at the end of the day, we don’t have anything to “show” for our work–we haven’t written anything polished or perfected–we’re “losing” the race.

But writing isn’t mass producing model Ts on an assembly line in a factory. We can’t measure creative work by conventional standards of productivity. A “productive” writing day might not produce anything. Sometimes you’ll spend hours writing 10 pages only to scrap them entirely; other times you’ll begin a piece with one idea only to realize it’s just not working.

Writing is blissful–but infuriatingly futile–work. As Oscar Wilde once wittily observed, a poet might squander an entire morning taking out a comma only to put it back in the same afternoon. If we judge our writing by how much we “get done,” we’ll end up in a padded room. Most days, we’ll get little done at all–if by “done,” we mean increasing words on a page.

But we get more done than we think. The 10 pages we had to toss might have been necessary for us to write but not necessary for our reader to read. Those pages might have taught us how to maintain the momentum of a story. Though they didn’t make the final cut, they might have given us invaluable insight into our central character or theme. A dead end might be a portal to an interesting passageway. An “unproductive” writing day might still be fruitful, even if it doesn’t exactly yield anything.

In his indispensable book The Mindful Writer, writer and essayist Dinty W. Moore confesses he once spent 4 years writing a 1,200 page book only to condense it to an 8 page essay. Could you imagine: dedicating nearly half a decade to a book only to salvage a scanty 8 pages?

If Moore had measured his productivity in terms of word count or a finished product, this would have been a colossal waste–he wrote 360,000 words and spent a significant portion of his life writing something that essentially went nowhere.

But in the writing life, there’s no such thing as a waste. All our “useless” pages add up to something. Moore’s full-length book only ended up being a brief essay but in the process of writing that book, he learned how to let go of that staunch “I must finish what I started” mentality, how to walk away when something is simply not working. Most importantly, those 360,000 words led him to discover the book he actually wanted to be writing.

So stop judging yourself and demanding you produce x number of words or pages a day. You are a human–not a soulless machine at the idea factory. There’s no reason to reprimand yourself if 90% of what you write ends up in the waste basket. And there’s certainly no reason to scold yourself if you “squander” your writing hours staring out the window daydreaming. As N. West Moss reminds us, everything is writing: the unsuccessful stories and books stuffed into drawers, staring at the ceiling, revising, research, plain old living.

“I always had this idea that I could only write if I was writing SOMETHING (i.e. something that would take the form of a final product like a book or an essay or a short story).” Felt this in my soul. This was SUCH a good read and so well-written! I agree 100% with your take on this topic.

I’m a fellow writer and blogger just trying to find her clan 😀 Subscribed.

LikeLiked by 1 person